Shiro Otani: A Ceramics Monthly Portfolio

by Rob Barnard

Published in Ceramics Monthly, 39(6), Summer 1991, 49-56.

The landscapes on Shigaraki jars have seasons also. Some jars are as bright and vivacious as a spring morning with green glaze cascading over a warm orange surface. Others are moody and withdrawn, barely touched with color--streaks of lavender and blue against dry gray clay. The 15th-century tea men who first brought those jars into their tea rooms knew how to read the landscape, just as they could read shading of ink on paper and see mountains and streams. In their mind's eye, they saw the valley that had made the jars.

--Louise Cort, quoted from Shigaraki Potters' Valley

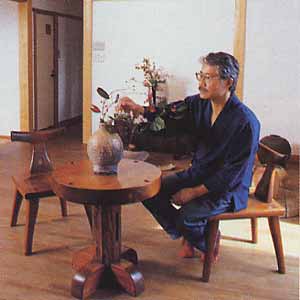

Otani with a 150-yr old Shigaraki jar outside his showroom

In the late 15th century, the tea master Murata Juko presided over a new aesthetic in the tea ceremony that transformed forever the way Japanese view the commonplace objects that surround them. This aesthetic, referred to as wabi cha, elevated rough, naturalistic and mundane objects into the realm of connoisseurship, which until then had been occupied exclusively by more elaborate and technically sophisticated pottery from China. Juko's poetic description of Shigaraki and Bizen as being "chilled and withered," and his linkage of this kind of appreciation with the search for spiritual enlightenment made wabi cha (and objects like the Shigaraki jars that embody it) a powerful philosophical and aesthetic force that still reverberates in Japan and is felt even here in the West.

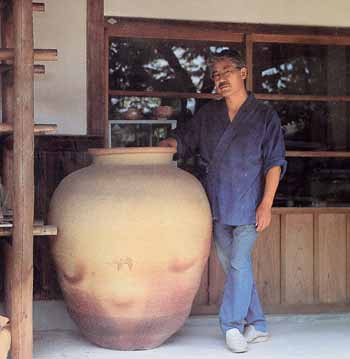

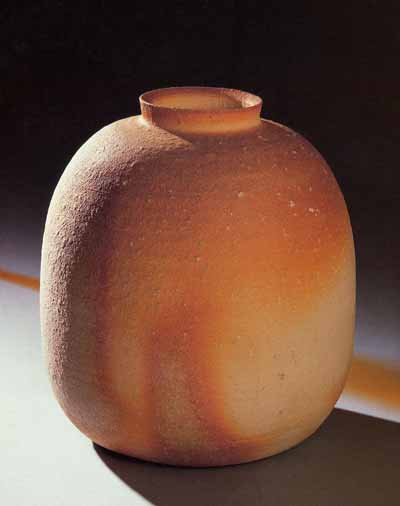

Vase 14 in/h

When Otani bought land and built his own wood-burning kiln across the road from Shigaraki's old imperial palace in 1973, he was totally absorbed with the idea of working in the tradition of Shigaraki that had developed around Juko's philosophy of wabi cha and was epitomized by those early Shigaraki tea wares. Shiro Otani's image of that tradition springs from and revolves around a special feeling he has for two elements he believes make Shigaraki ware special. The first is the material itself: a coarse, white, highly refractory clay, flecked with feldspathic rocks that appear to erupt over the entire surface of the pot when it is fired. The second is the interaction of the clay with ash and flame in the lengthy and intense wood firing that gives Shigaraki pottery its distinctive surfaces, ranging from soft pinks and oranges to crusty gray and toasted brown covered with transparent olive green glaze. Although other places in Japan also have a long history of wood-fired ware, Shigaraki's clay and the unique way it interacts with fire have made it recognizable worldwide.

Hanging Vase 8 in/h

Up until the mid 1970s, Otani expended all his energy and resources learning how to make and fire work that fit his image of traditional Shigaraki ware. Then, he experienced a kind of crisis in faith and began to fear that it was impossible as a modern artist to make any impact on the Shigaraki tradition. It seemed to him that there might not be any room for his personal aesthetic investigations. Otani struggled through the early '80s to find his own voice, at times even exploring possibilities outside the Shigaraki tradition. In 1980, for example, he applied for and received an exchange fellowship from the Japanese Ministry of Culture and the National Endowment for the Arts. He spent a year at the University of Tennessee, and a brief period at Arrowmont School for Arts and Crafts, where he built and fired a Japanese-style, woodburning anagama.

Then, he experienced a kind of crisis in faith and began to fear that it was impossible as a modern artist to make any impact on the Shigaraki tradition. It seemed to him that there might not be any room for his personal aesthetic investigations.

Although his stay in the U.S. was personally gratifying--allowing him to meet, exchange ideas and form friendships with many American craftspeople--it only created more confusion in his mind about exactly what kind of work he wanted to make. The freedom to experiment exhausted him. He started down numerous paths of inquiry only to reach as many dead ends. It was a time when he changed his mind a lot, a time when he was often unsure of himself', and his work by his own admission reflected this state of uncertainty. This period shows, though, perhaps more than anything else the strength of Otani's desire to find his own voice by taking the kinds of risks that most Japanese potters would find unacceptable. This desire not only led him to live and work in an alien culture where his cultural preconceptions were severely challenged, but also forced him to focus on that part of his work where the superficial idiosyncrasies of culture cease to be relevant. Otani's approach, both then and now, reminds me of something Walt Whitman said in Leaves of Grass: "I reject none, accept all, then reproduce in my own form."

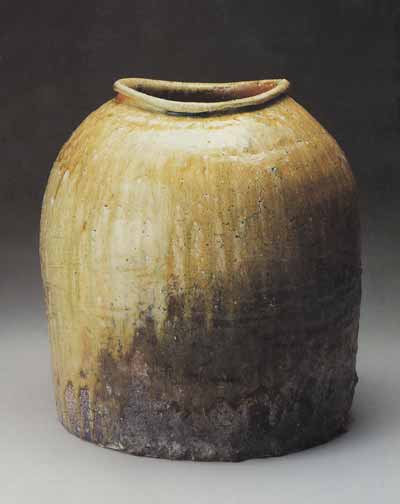

Vase 12in/h

In 1985, Shiro Otani returned to Arrowmont for three months to make work for a Tokyo exhibition. In the catalog for that show, he wrote: "Since Shigaraki ware is unglazed and carries no external design, its quality can only be expressed in such abstract words as 'taste' or 'sense of understated elegance.' Within these parameters, I asked myself what it was that I could add to Shigaraki. Looking out over the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, I rethought these problems as if standing outside myself."

This idea of harmony, which eschews the supercilious and egotistical in favor of the subtle and unassuming, forms the cornerstone of Otani's idea of beauty.

There was no sudden moment of enlightenment where he clearly saw the direction his work should take. Instead, certain elements and concepts slowly seemed to reassert themselves in his mind and began to take on renewed significance. One of the most important of these was the concept of harmony. A vase, for example, must not only accommodate the flowers it was made to contain, but also fashion a moment in space where those flowers together with the vase create an aesthetic or spiritual resonance that either of them alone would have been unable to achieve. This idea of harmony, which eschews the supercilious and egotistical in favor of the subtle and unassuming, forms the cornerstone of Otani's idea of beauty. This kind of harmony, however, should not be confused with the easily appreciated, predigested sort of beauty that lacks psychological texture and emotional tension. Instead, it is much like the imperfect perfection of nature--fragile, raw, full of contradictions--that is never redundant and always compelling. Shiro Otani tries to emulate these qualities in his own work by the continuous denial of the superfluous, as well as his insistence on searching for beauty in the basic, rather than trying to find it in the lavish and/or the extravagant.

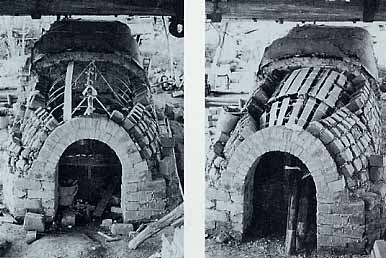

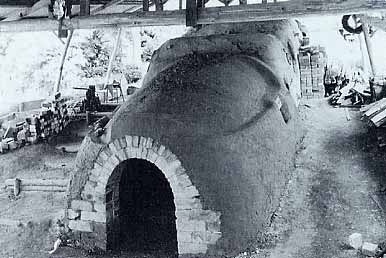

Kiln Construction

Anagama section in front and rear Noborigama-like chambers

One of the best examples of melding this notion of harmony with his desire to fashion a personal statement inside the Shigaraki tradition is his "broken" ware. Begun in the early '80s, these plates and vases were made deliberately to crack or break in the long firing.

1981 Plate 18 in/h

[Otani struggles] with the dilemma of what it means to be modern and yet feel mysteriously drawn to primordial forms of expression.

Otani, like all modern potters who are engaged in the struggle to fashion meaning rather than mere utensils, is involved in creating objects that actively challenge our imagination and point beyond themselves to ideas, feelings and emotions that are part of our cultural as well as our personal lives. A vase, for example, may appear mannered and self-conscious when compared to the deliberately crude modeling of early Shigaraki tea wares that were trying to affect the rusticity of older utilitarian jars. By playing, however, to our traditional view of Shigaraki, while at the same time contradicting that view, Otani forces us to reexamine our preconceptions about how beauty can be expressed inside that tradition. Some of Otani's works are more aggressive in this respect than others, but all are about his struggle--and we could say our own--with the dilemma of what it means to be modern and yet feel mysteriously drawn to primordial forms of expression.

Flame-Color Vase 16 in/h

Like tea-ware potters of the late 16th and early 17th centuries, who built on the tradition of Shigaraki that preceded them, Otani has struggled to expand on what he inherited. He has taken that history and combined it with his own modern vision to give us work that somehow satisfies both our sense of continuity with the past and our desire to explore the possibilities of the future.

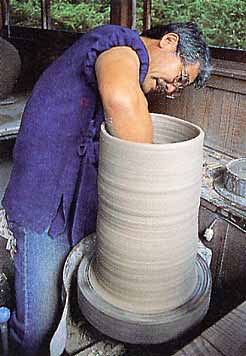

Otani throws clockwise

Otani's Studio in Shigaraki